Having won just one of their last six league games, losing five, SSV Jahn Regensburg now sit in eighth place in 2. Bundesliga on 28 points.

However, things are tight at the top of Germany’s second-tier, as Die Jahnelf are just two points away from third place 2. Bundesliga’s promotion play-off place.

The team sitting in this position at the end of the campaign will face the team that has finished 16th in the Bundesliga for a place in next season’s German top-flight.

Germany has been a fertile breeding ground for elite coaches over the past 15 years or so.

During that time, Champions League-winning managers such as Liverpool’s Jürgen Klopp, Chelsea’s Thomas Tuchel, and Germany’s Hansi Flick (who won the 2019/20 Champions League with Bayern Munich) all rose to prominence.

The fact that a team has won Europe’s premier competition under one of these German coaches in each of the last three years after they’d spent the majority of their formative coaching years in their native country highlights this fact.

Nationality doesn’t determine whether one becomes a good coach.

Still, it says plenty about the environment in which these coaches have been produced, as well as the prominent coaching trends in Germany.

In the current age, football at the highest level will always take inspiration from a variety of sources and footballing styles, not just one, so it’d be inaccurate to say ‘the German style’ is the best right now.

Still, I would say that we’ve seen a rise to prominence of more intelligent pressing systems at the top level over the past decade.

Coaches under a heavy German influence, including the aforementioned trio, have all led teams that deploy highly intelligent, organised pressing systems.

Additionally, the three aforementioned coaches tend to lead teams with very intense defensive systems.

So, they’re excellent at coaching intense yet organised and intelligent systems.

This has proven to be a lethal combination.

There remains an abundance of exciting coaches currently making their way through the ranks in Germany, one of whom leads Jahn Regensburg in 2. Bundesliga: Mersad Selimbegović.

From Bosnia and Herzegovina, the former defender has been in Germany since joining Jahn Regensburg as a player in 2006.

He spent six years at the club as a player before becoming an assistant at Jahn Regensburg II in 2012.

After four years in that position, he took charge of Jahn Regensburg U19 for the 2016/17 season before becoming Jahn Regensburg’s first-team assistant manager from 2017 to 2019, where he worked alongside RB Leipzig’s current interim manager, Achim Beierlorzer.

He went on to replace Beierlorzer as first-team manager in 2019 and has thus far led Jahn Regensburg to 12th place (2019/20) and 14th place (2020/21), with the club currently sitting in eighth place, having been challenging at the top of the table for the entire first half of the 2021/22 campaign.

Selimbegović’s side have been an interesting one for me to follow since the beginning of the 2021/22 campaign, as they’ve been a real threat at the top of the table despite operating with a relatively small budget and having the second-youngest team (25.2 average age) in the league, while Selimbegović has been able to mould the team very much into his image, with Die Jahnelf displaying a lot of clear, recognisable characteristics that would come from the head coach which have defined their impressive start to the season.

As a result, I’m excited to write about the 39-year-old manager for this magazine and shine a light on someone who I believe has a very bright future in the game.

This tactical analysis aims to provide insight into Selimbegović’s overall strategy and tactics — and the results of those strategies and tactics, both good and bad — based on his Jahn Regensburg side’s performances this season.

Separate analyses of each individual element of his side’s game and their performances across different phases of play would also be valuable and interesting.

Still, this analysis aims to paint a clearer picture of Selimbegović’s overall football philosophy, using his Jahn Regensburg team as a basis.

All stats and data in this tactical analysis have come from Wyscout unless stated otherwise.

Mersad Selimbegović Build-Up And Progression

Selimbegović’s side is not very possession-based; they’ve kept an average of 49.3% possession this term — 11th in 2. Bundesliga.

They’re a far more transition-based side, in general.

Jahn Regensburg’s 345.87 passes per 90 (sixth-lowest in 2. Bundesliga) and 12.6 passes per minute of possession (fifth-lowest in 2. Bundesliga) reflect this too.

They rank at the other end of the table for long ball frequency, however, with 56.6 long balls per 90, placing second in 2. Bundesliga.

Jahn Regensburg have also got 61.2% long ball accuracy for this season, though, so this isn’t a case of Selimbegović instructing his team to simply lump it long or the players just clearing it upfield under pressure — the long balls are part of the plan.

In this section of my analysis, I will examine the 39-year-old coach’s team, identifying excellent opportunities for progression via long balls, along with other important elements of their play in the early possession phases.

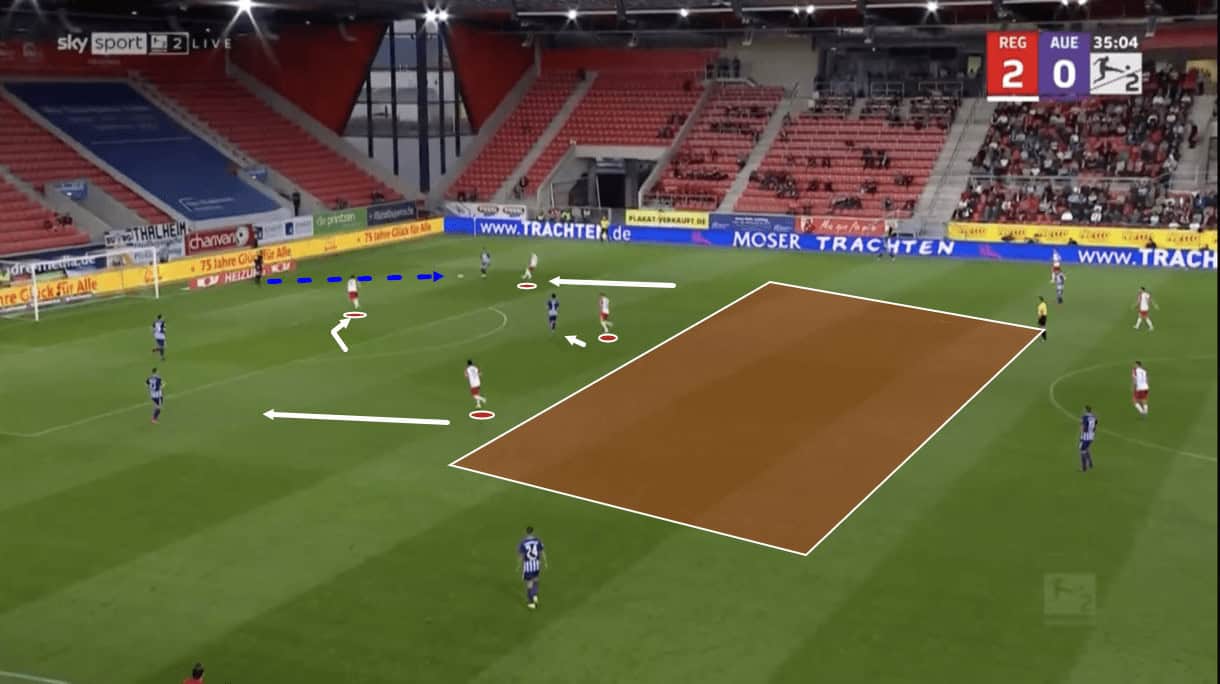

Figure 1 shows an example of Jahn Regensburg’s typical shape during the build-up phase, as Selimbegović’s men look to play through the thirds.

Yes, Selimbegović’s team isn’t the most possession-based one in 2. Bundesliga, but they still aim to build out from the back via short passes regularly.

Their aim when doing so is to draw opposition bodies upfield — with 2. The Bundesliga is a very defensive-aggressive league, where many teams prefer to press high from the front and exploit the space behind the defenders once it opens up.

When Jahn Regensburg build up their attacks from the back via short passes, it’s common to see them shape up as we see them in figure 1.

Firstly, Selimbegović primarily sets his team up in a 4-2-3-1 base shape, with the somewhat similar 4-4-2 coming in second.

Either way, he tends to set up his side in a back four, two deeper midfielders, and a front four.

In possession phases, the centre-backs tend to get very wide, effectively occupying more traditional full-back positions.

This gives the goalkeeper short-passing options while making them more difficult for the opposition to cut off than if they were positioned more centrally.

If the opposition attackers split wide to mark the centre-backs, space may open up centrally for a midfielder to exploit.

With teams generally preferring to protect the centre first and foremost, this leads to a pass to the wide centre-backs becoming a very viable option at the beginning of build-up, which was the case in figure 1, where we see Jahn Regensburg’s right centre-back on the ball after just receiving it from the ‘keeper.

Meanwhile, Jahn Regensburg’s full-backs push high to get in line with the midfielders — usually, the highest of the two midfielders, as those two players should stagger to make themselves more difficult to mark while creating better passing angles for their teammates and themselves in the process.

So, the centre-backs split wide of the ‘keeper, the full-backs create the following line along with the midfielders, and this leads us to the front four, who also tend to stick together very closely.

They don’t operate in a defined line of four but tend to be positioned close together, enjoying the freedom to vary their movements to make themselves more difficult to mark and to exploit space as it appears.

Sometimes an attacker will drop while another looks to provide depth by running in behind the opposition’s backline, for example.

These varying movements are more difficult to defend against.

It’s important, however, that these players are positioned closely together for several reasons, including:

- Help them link up quickly via short passing sequences

- Help them to win second-balls if their deeper teammates opt to send it long

- For counter-pressing in case the ball is lost.

This shape and these tactics, as well as the players’ application of them, can create some issues for Jahn Regensburg in terms of progression.

For example, in Figure 2, we see Jahn Regensburg building out from the back in a very similar way and very similar position to what we saw in Figure 1.

However, a major difference on this occasion was that the midfield didn’t stagger; instead, both central midfielders remained on the same higher line.

This created a significant gap between defence and midfield, stifling Jahn Regensburg’s ball progression and underscoring one key reason this midfield stagger is so crucial.

The double pivot acts as a link between defence and attack; if they don’t perform their role exactly as previously described, it can lead to a significant disconnection between midfield and defence.

While making Die Jahnelf’s progression more difficult, this also isolates the defenders and puts them in greater danger of being dispossessed in a dangerous position due to opposition pressure, as seen in Figure 2.

Furthermore, if both midfielders drop deep or if one of the two midfielders drops a lot deeper than the other, this can still create a big disconnect between them and the attack or between each other, thus stifling Jahn Regensburg’s progression.

This can happen at times with Jahn Regensburg’s front four remaining so high and close together — a tactic that can be helpful when the ball gets to the forward line, but potentially unhelpful in trying to make it to that point.

Sometimes, when Selimbegović’s side makes it into the centre with one of the midfielders, the player lacks forward-passing options because the attackers are so high, and this puts a lot of reliance on the midfielders’ carrying ability to drive the team forward.

At times, you could argue that it’d be more beneficial for Jahn Regensburg to drop more bodies deep to avoid their midfield getting overloaded or too much space opening between defence and midfield/midfield and attack while trying to progress.

Still, they like to keep the long-ball option open, which the closely positioned front four is important for.

Their patient build-up at the beginning, when they opt for it, helps draw opposition defenders forward and create more space for the front four upfield to work with later when they do decide to hit the long ball, which is where these two elements of their play connect to each other.

At times, Jahn Regensburg puts too much pressure on the ball carrier, leading to the long ball being cut off.

They could be quicker to hit the long ball when this happens, though, of course, it will inevitably happen when playing against other teams with their own really aggressive and organised pressing systems.

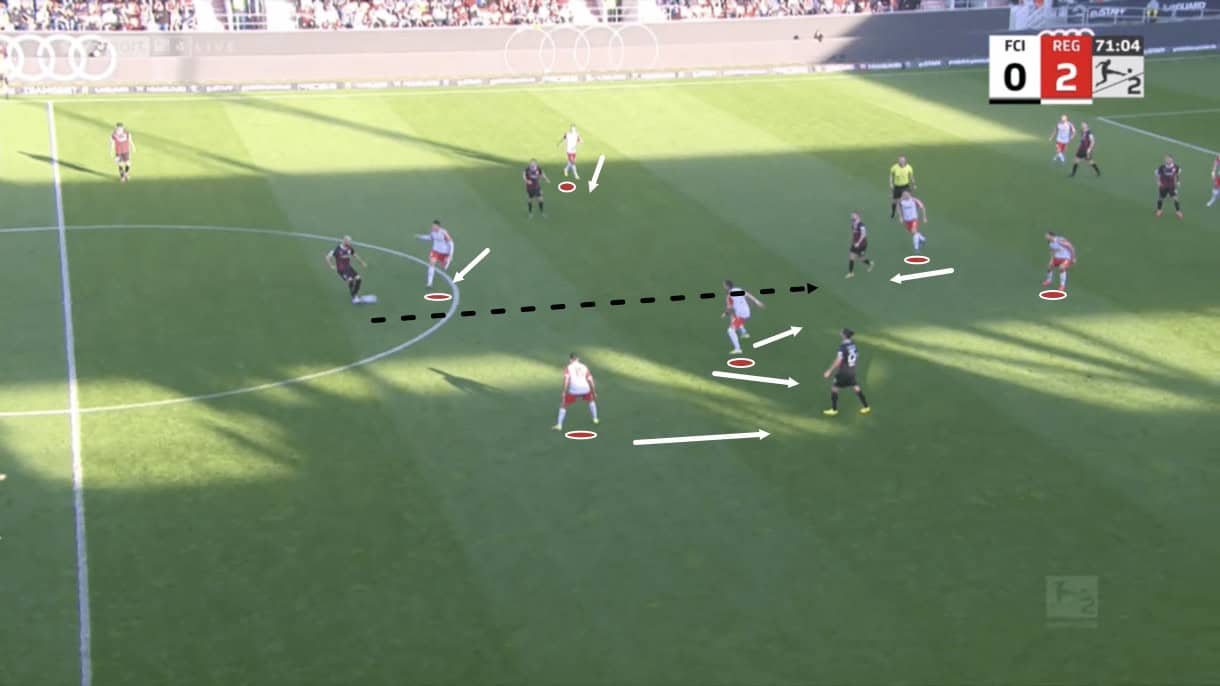

Figure 3 shows an example of Jahn Regensburg’s front four reacting to a long ball being sent forward (along with one of the central midfielders who is driving forward to join the attack).

The centre-forward has managed to force the opposition defence backwards with his run into the channel between two central defenders, with which he threatens to take the ball down and drive through on goal alone.

Thanks to his efforts in driving the backline backwards and the long ball that capitalised on the opposition’s midfield being drawn higher through Die Jahnelf’s prior play, lots of space was created in front of the opposition’s backline for the attackers following the centre-forward to exploit, which is exactly what happens after the centre-forward neatly knocks the ball back to the following attackers after meeting the long ball.

It’s very common to see Selimbegović’s side aim to use the closely-positioned front four like this, with a long ball sent to the furthest forward attacker, and that ball then knocked back to the others to exploit space between the lines.

After one of the attackers receives the ball, the others will burst forward to try and overload the opposition’s backline and to provide the carrier with runners.

This element of their attacking play has helped them to score plenty of goals this season, with Jahn Regensburg currently boasting the third-best goalscoring record (35) of any 2. Bundesliga team this term.

Mersad Selimbegović Chance Creation/Wing Play

That last statistic — Jahn Regensburg’s stellar goalscoring record in 2021/22 — speaks for itself, and it’s clear that Selimbegović’s team has been great value for money going forward this term.

Why have Jahn Regensburg been scoring so many goals though?

And why are they outperforming their xG (25.5) so heavily?

Part of this is down to the types of goals they’ve specialised in, as Jahn Regensburg rank first in 2.

Bundesliga for goals from outside the box (9) and headed goals (8).

Some of the reasoning for that comes down to Jahn Regensburg enjoying their fair share of luck, along with their players’ excellent finishing.

Still, Selimbegović’s offensive system has also played a crucial role in creating the right conditions for these types of goals to be scored so frequently.

Before moving on, it’s also worth noting that while Selimbegović has helped his team to outperform their xG, this level of overperformance is still unlikely to continue in the long run and creating more high-quality chances, as opposed to just ‘chances’ should be on the Bosnian’s agenda.

For example, situations like the one we saw in Figure 3, where Jahn Regensburg’s attackers are exploiting the space between the lines, can create excellent conditions for a long shot, giving an attacker acres of space and time after carrying the ball forward to pick his spot in goal.

This is something Selimbegović’s players have benefited from this term; they’ve enjoyed opportunities to collect the ball in space between the lines where they can carry it forward just to the edge of the area.

Being in a central position on the edge of the box with time and space to line up a shot is a more favourable condition than the average shot from outside the area will be taken in, so this has helped them to score more goals than any other team from these positions.

As for headed goals, Jahn Regensburg’s wing play and crossing styles go some way to explaining their efficiency in this area.

Firstly, Die Jahnelf don’t play the most crosses in 2. Bundesliga by any means; they’ve actually played just 12.53 crosses per 90 this term — the third-lowest crosses of any 2. Bundesliga side.

Their crossing accuracy (37.4%) is better; however, it ranks them eighth in the league.

What’s more relevant than that, though, is their typical style of crossing.

Jahn Regensburg doesn’t play a ton of low driven crosses or low cutback crosses from the byline.

They don’t actually spend that much time in the opposition penalty area at all and don’t exhibit a lot of patience in their attacking play, instead playing with a really high tempo and lots of directness, relying on their ball carriers to dribble through the opposition defence and runners to provide good options for direct line-breaking passes.

In terms of their crossing, while they don’t play lots of lower crosses from closer to goal, they do play plenty of lofted crosses from wide positions and early crosses from deep positions.

Unlike the lower crosses, these cross-types don’t typically set up normal shooting opportunities at the player’s feet, but instead set up headed opportunities.

This places lots of importance on the heading ability of Jahn Regensburg’s forwards and the crossing ability of the wingers and full-backs.

Equally as important, though, is Selimbegović’s instructions, coaching, and motivation methods to ensure that the opposition penalty box is flooded with bodies when their crosses are coming in.

Die Jahnelf are adept at overloading the opposition’s penalty area for their crosses, which plays a key role in their impressive crossing accuracy and headed goals record this term.

They’ll typically aim to set the full-back up as the crosser and get all members of the front four, along with possibly one midfielder, in the box to attack the cross.

This can be especially dangerous in offensive transitions as the opposition’s defensive shape won’t be so organised, and an overload can be more easily achieved as a result.

At the same time, this requires a lot of the Jahn Regensburg attackers in terms of the work rate and effort they must apply to flood the box in transition, as they must quickly move upfield from a previous defensive position.

Wing play is an important part of Jahn Regensburg’s general attacking play, however, not just transitions.

In the ball progression and chance creation phases, it’s common to see Jahn Regensburg overloading the wing with the aim of either breaking through the defensive structure on that wing via some intelligent and crisp passing play or by drawing the opposition to this side of the pitch so heavily that an opportunity to switch is created.

Figure 4 shows an example of Die Jahnelf overloading the left wing, a typical structure they create in these situations.

Jahn Regensburg’s typical attacking shape in the progression phase becomes a 2-4-4, with the front four remaining narrower and closer together, the full-backs providing the width for their team on the wings, either side of the central midfielders who’ll shift from side to side, offering support depending on where the ball is, and the centre-backs remaining deepest.

However, when looking to build through on the wing, it’s really common to see one of their centre-backs (the left centre-back on this occasion) pushing higher to act as the deepest member of a wide diamond on that wing, where he’ll link up with the full-back (the widest part of the diamond on that wing), the winger (in the half-space) and the near central midfielder (the narrowest part of the diamond, positioned adjacent to the full-back).

This is what we see in Figure 4, and it can create combinations for progression, such as centre-back to winger to full-back or centre-back to winger to central midfielder.

On this occasion, however, the opposition played in a very space-oriented manner, congesting the area around the ball on this wing and preventing Jahn Regensburg from playing through on this side.

As a result, the left centre-back opted to send the ball back to his partner, the right centre-back, now positioned as if he were a sole central defender, as we see in figure 5.

Through this centre-back, Jahn Regensburg were able to exploit the opposition’s narrow space-oriented defensive shape as the right centre-back switched play to the right wing, where Die Jahnelf’s right-back was waiting to burst down the underloaded wing, which he did after receiving the ball, taking his team into the final third and setting up a great crossing opportunity.

This passage of play highlights a lot of important things in Jahn Regensburg’s offensive play, including the centre-backs’ aggression in pushing forward into the opposition half when the team is in a period of possession on their wing (not just for direct progression through them, but also to initiate the switch if progression proves too difficult on that wing) and the full-backs’ wide positioning on either wing, either providing support to the overload or an option for the switch, both of which we saw in this example and both of which are important for setting up crossing opportunities for Selimbegović’s side.

The full-backs play a key role in this team’s chance creation; they must also be constantly getting forward when the winger is in possession out wide to provide an option on the overlap and double up on the opposition full-back, as shown in Figure 6.

Again, this is intended to create a crossing opportunity either for the full-back, should they find space with the opposition full-back focusing on the winger, or for the winger if the overlapping run draws the opposition full-back away.

This highlights the importance of the relationship between Selimbegović’s wingers and full-backs — they’re very much a partnership on the wing.

They must communicate well and have a strong understanding of each other.

This also shows us the importance of the full-backs’ work rate in Selimbegović’s team, as they must be prepared to work up and down the flank all game, especially in transitions, which Jahn Regensburg tend to rely on and thrive in.

Mersad Selimbegović Defensive Phases

Selimbegović’s team isn’t among the highest pressing sides in Germany’s second-tier.

Though their PPDA of 11.16 for 2021/22 isn’t particularly low by any means, it is among the lowest in 2. Bundesliga, ranking 12th, which says something about their style but may say even more about the preferred styles of other teams in the league.

Either way, Jahn Regensburg isn’t the most aggressive or intense team in the league; they are actually among the least intense.

However, Jahn Regensburg deploys an organised position-oriented press that, although it has some weaknesses, has played a key role in their success this season, with transitions playing an important part in the team’s offensive success, and this pressing system being crucial for creating those opportunities for offensive transitions.

We see an example of Jahn Regensburg’s front four engaging the opposition’s backline during the high block phase in Figure 7.

In this phase of play, Jahn Regensburg’s tight-knit front four is yet again important; the players remain close together, pressing as a unit.

Each individual’s own defensive actions are also very important, though.

For example, as this ball is played to the left centre-back from the goalkeeper, Die Jahnelf’s centre-forward presses quickly and intelligently.

He curves his run to ensure that before closing down the new ball carrier, he’s blocked off the passing lane across goal to the other centre-back.

At the same time, this helps him gain better access to the goalkeeper if the ball is sent back there, and this slight movement essentially cuts off half the pitch for the opposition.

With the other centre-back in his cover shadow, the centre-forward is now freer to press the carrier without allowing passing options around him to open up.

Meanwhile, Jahn Regensburg’s ‘number 10’ gets tight to the opposition’s deepest ball-near midfielder, their ball-far winger gets tight to a deep ball-far midfielder while retaining some access to the other centre-back, and the ball-near winger quickly and aggressively closes down the centre-back in possession as he receives the ball, reducing his decision-making time on the ball and making it more difficult for this player to turn and send the ball backwards, meaning he’s left with essentially one option — sending the ball out wide to the full-back.

This pass is a significant pressing trigger for many teams, including Jahn Regensburg.

As that pass is played, Jahn Regensburg’s full-back sprints upfield to close down the opposition full-back, and this leads to the scene we see in figure 8, where the opposition’s full-back is on the ball with nowhere to go while being aggressively closed down by Jahn Regensburg’s full-back.

Thanks to their organised pressing to force this pass out wide in the first place, Jahn Regensburg’s front four are positioned really well to basically block off any sideways or backwards passing options for the carrier and as play moves on, the player is forced to play a rushed, inaccurate long ball that leads to a turnover, albeit in a deeper area than we see Jahn Regensburg pressing here.

As previously mentioned, this organized and aggressive pressure is crucial in both stifling opposition progression and creating counter-attacking opportunities for Die Jahnelf.

Therefore, it’s a key part of Selimbegović’s game plan that his team frequently executes to a high level, as seen in Figures 7-8.

One negative of Jahn Regensburg’s high pressing, however, is the amount of space it allows to open up between the front four and the midfield.

At least one of Jahn Regensburg’s deep midfielders will advance into a higher defensive position if an obvious threat moves into the space marked with a red box in Figure 9.

Still, generally, they tend to remain deeper, preferring to protect space in front of the backline rather than space behind the forward line.

Similar to the build-up and early progression phases, some disconnection can occur between Selimbegović’s forwards and midfield, which the opposition can exploit.

This can be done by carrying the ball into the red box by beating the forwards 1v1, or by passing into it quickly via intelligent passing and movement.

As previously mentioned, the front four always remain together, defending as a unit, and this helps them to pose a defensive threat to the opposition when pressing high, even with this space open behind them, because they’re good at closing off near passing options and pressuring the ball carrier in the way I discussed while analysing the previous passage of play.

We see a very similar press in action in Figure 9.

However, it’s worth noting that this space behind the front four can be exploited and may be a worthwhile target for opposition teams inthe future after drawing the front four high via their build-up, as the midfielders behind are more committed to protecting deeper space.

It’s common to see Jahn Regensburg dropping off to roughly the halfway line, if not deeper, before initiating their press, even though the previous two passages of play showed Selimbegović’s side engaging the opposition high, around their own penalty area.

This won’t be the case if, for example, the forward fails to cut the pitch in half well enough, or the near passing options aren’t all adequately cut off, or the ball carrier is given too much space to start moving forward.

In these cases, Jahn Regensburg will likely drop deeper before engaging the opposition, so Selimbegović is happy for his side not to go hell for leather at all times inside the opposition’s half, prioritising organisation and the right conditions over all-out intensity.

Figure 10 shows an example of Jahn Regensburg’s 4-2-3-1 formation during the mid or low block phases.

In these phases of play, the midfield and forward lines are far more compact, both horizontally and vertically, which better protects the centre of the pitch and makes it much more difficult to play through than in Figure 9.

They continue to defend in an organised, position-oriented zonal system when playing deeper, with the centre-forward typically tasked with leading the press, while the ‘10’ and wingers focus on marking central short passing options.

On this occasion, in Figure 10, we see the opposition attempting to play through midfield despite Jahn Regensburg’s heavy coverage in this area, and what follows both provides an example of Jahn Regensburg’s defensive organisation, preparedness, concentration, and efficiency, as well as specific details on the roles that the deep midfielders play in defensive phases.

As the ball was played into midfield in figure 10, the opposition receiver was dropping deep, followed by one of Jahn Regensburg’s deep midfielders, and was thus forced into a rushed pass to another midfielder alongside him.

However, as Figure 11 shows, partly due to Jahn Regensburg’s tight defensive structure that gave the opposition no space in this area and partly due to the pressure from the holding midfielder behind the receiver, the rushed pass was misdirected and created a 50/50 between the intended receiver and Die Jahnelf’s other holding midfielder.

As the pass was played, Jahn Regensburg’s left holding midfielder jumped into action.

They entered the 50/50 aggressively to regain possession for his side and set up a counter-attack for Selimbegović’s men.

This passage of play shows the benefits of having such a compact midfield structure, as it makes this area of the pitch far more difficult for the opposition to play through.

Additionally, this shows the important role Jahn Regensburg’s holding midfielders play in jumping into defensive action when a real threat appears in front of them.

Selimbegović places a lot of trust in his midfielders to make the right decisions on when to jump and when to sit.

They are generally more reserved players whose discipline is valued in this team, but need to be ready to burst into action when required, as we saw here, to either follow threats when they drop in between the lines or to contest winnable 50/50 duels.

Mersad Selimbegović Transitions

I mentioned at the beginning of this tactical analysis that Selimbegović’s team is a more transition-based one, and that means that counter-attacking is a very important part of their strategy and tactics.

Equally, while we’ve seen that Jahn Regensburg are a really organised team in their settled defence, especially the mid-block and low-block, they have some weaknesses in transition to defence.

In this section of analysis, I’ll highlight the good and the bad about Jahn Regensburg’s performance in offensive transitions and defensive transitions — two really important phases of play for Selimbegović’s men.

Starting with defensive transitions, Figure 12 illustrates another crucial aspect of the holding midfielders’ roles in this team: they must be prepared to act aggressively to close down opposition ball carriers as the counterattack kicks off.

If Jahn Regensburg lose the ball in an offensive phase, likely, they won’t have lots of bodies behind the ball to clean up the mess as they would’ve had runners ahead of the ball carrier attacking the opposition’s backline.

As a result, the central midfielders can become overloaded quite quickly in this phase of play and Selimbegović asks a lot of them.

In the example shown above, the right holding midfielder must close the ball carrier down as he receives a pass from the teammate who’d just regained possession.

This is another example of the holding midfielder entering into a 50/50 challenge — he must try to close down the carrier before he exploits space in midfield to launch his team’s counter-attack against Die Jahnelf.

However, this 50/50 favours the opposition more than it does Jahn Regensburg, with the ball being slightly closer to the intended receiver and the opposition having an overload on this occasion, unlike in figures 10-11 when settled Jahn Regensburg had full control over the centre of the pitch.

As play moves on, we see the opposition swiftly pass the ball around the pressing midfielder, setting up an opportunity to drive through midfield and attack Jahn Regensburg’s weakened defence in transition.

We see another example of what I mean when I talk about Jahn Regensburg not having tonnes of bodies behind the ball to protect midfield in transitions at all times in Figure 13.

As mentioned earlier, Selimbegović likes his team to attack quickly and with intensity, which makes for some exciting end-to-end games and suits his team well in the offensive phases.

However, this can also lead to a lack of control over midfield, especially when, as was the case just before figure 13, the ‘10’ is carrying the ball forward with the wingers and centre-forward providing options ahead of him.

This is because if that player then loses the ball, again, as was the case in figure 13, lots of space exists in midfield behind the carrier for the opposition to exploit on the counter, and immediately, four players (the ‘10’, wingers, and striker) are taken out of the game.

A more patient, controlled game would likely see Jahn Regensburg be less open on the counter and with a better shape for counter-pressing. Instead, Selimbegović wants his team to attack quickly, which is fine, but has the aforementioned weakness in transition to defence that they must then deal with.

As for offensive transitions, this is where I’d argue Selimbegović’s team is at its most dangerous.

Figure 14 provides an example of Die Jahnelf in transition to attack, having just regained possession inside the opposition’s half.

This shows another benefit of the front four being positioned so closely together.

When they win the ball back, it leads to easy link-up play and the possibility of breaking through the opposition’s backline very quickly with intelligent, swift passing and movement.

Here, the left-winger sent the ball back to the ‘10’, who then got his head up to look for the runners ahead of him.

The centre-forward made a run off towards the centre from the right, dragging the opposition’s left centre-back away with him in the process, which created space between the left centre-back and left-back for Jahn Regensburg’s right-winger to target with his run, and the passer to target with his pass.

As play moves on from here, that’s exactly what happens, and we see Jahn Regensburg’s right-winger played through on goal at the end of this quick but deadly little three-pass transitional move.

It’s common to see Selimbegović’s side look to transition quickly through the centre.

From deeper positions, we often see their goalkeeper roll the ball out quickly into one of the holding midfielders’/wingers’/10’s feet to get them driving the team forward via a progressive carry.

We see another example of Jahn Regensburg counter-attacking the opposition through midfield in Figure 15.

Just before this image, Die Jahnelf regained possession slightly deeper in midfield, and as play progressed, they quickly sent the ball through the centre to a more advanced player, who we now see on the ball in figure 15.

As this player attracted opposition bodies towards him, he knew to look out wide where Jahn Regensburg’s right-back was bombing forward to exploit the acres of space open on the wing, which is what happens as play moves on from figure 15.

We see a through ball sent into the runner’s path.

This passage of play is a testament to Selimbegović’s coaching, as his team first regained the ball through their defensive system, then quickly played it into a dangerous area — the underloaded wing — where the marauding full-back could come into the game.

The attacker knew to look out wide for this player’s movement immediately because of their tactical familiarity with Selimbegović’s plans and requirements for the active full-backs.

This passage of play shows an example of this team’s excellent tactical understanding, as well as the full-back’s excellent performance of the demands placed upon him during the offensive transition, a key phase of play for this team.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I hope my tactical analysis has shed light on what I believe makes Mersad Selimbegović a tactically interesting and exciting manager with a bright future ahead of him.

The 39-year-old Bosnian leads an organised and tactically intelligent team that thrives in transition to attack, settled defensive phases, and heavily endorses wing play in the chance creation phase.

Selimbegović is happy for his team to play it long a lot, but also oversees plenty of short-passing build-up play to create space upfield that they can exploit.

He likes fast, direct, and aggressive play on the ball, with an emphasis on wing play and early/lofted crosses, while he sets them up to be organised and disciplined in defensive phases.

As weaknesses, I think Selimbegović’s team can be exploited in the high block when they’re less compact, particularly during the build-up, when disconnection occurs between defence and midfield/midfield and attack, and in defensive transitions, where they can leave the midfield too exposed.

![Lazio Vs Napoli [0–2] – Serie A 2025/2026: How Antonio Conte Tactics Exploited Structural Flaws – Tactical Analysis 20 Lazio Vs Napoli [0–2] – Serie A 2025/2026: Maurizio Sarri Zonal Marking Weaknesses And Unsuccessful Attacking Choices – Tactical Analysis](https://totalfootballanalysis.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Lazio-Vs-Napoli-tactical-analysis--350x250.png)

![Manchester City Vs Chelsea [1–1] – Premier League 2025/2026: How Chelsea Held Firm After Enzo Maresca Exit – Tactical Analysis 21 Man City 1-1 Chelsea - tactical analysis (1)](https://totalfootballanalysis.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Man-City-1-1-Chelsea-tactical-analysis-1-350x250.png)