Rennes are having a slightly underwhelming season. Last season they finished third in Ligue 1, and as a result, competed in the Champions League this campaign. Yet they finished fourth in their group, and currently sit 10th in Ligue 1 at the time of writing. If they win their game in hand they will move seventh, and this would put them within three points of fifth-placed RC Lens. However, their poor 2021 is going to cost them European football this season, having garnered just seven points from their ten league games this calendar year. Rennes have scored seven goals in these ten fixtures and conceded 14 – obviously a worrying trend.

Despite their concerning league form, Rennes are one of the most dominant possession teams in the league. They have averaged 58.2% possession per game, the second-highest amount in the league. On top of this, they have the second-highest pass accuracy too, with 87%. They are a patient side in possession, after all, how could you not be with such a high possession share. Yet they are still a forward-thinking side and aren’t employing a death-by-passing, tiki-taka style of football. They have averaged 76.9 progressive passes per 90, which is the highest amount in the league, and their 80.3% completion of these kinds of passes is highly respectable.

As such, I was interested in giving a tactical analysis of their build-up play, particularly how they use a fluid formation to structure it.

Formation and personnel

Whilst they’ve used a few different formations this season, there is a clear preference for a back four and a central midfield three. We can see this by observing their three most used formations, (4-1-4-1, 4-3-3, and 4-2-3-1), all of which incorporate these two structures. We will be looking at their build-up play in their 4-1-4-1, but the differences between this and the 4-3-3 are just based on how far forward the wingers push.

As for personnel, their most commonly used line-up looks like in the following image. Premier League fans will be all too familiar with Steven Nzonzi, who is an ever-present in this side, most often used as a holding midfielder. Eduardo Camavinga is Rennes’ most high-profile player. The 18-year-old French midfielder is an outstanding talent, clearly destined to play at the highest level in the game.

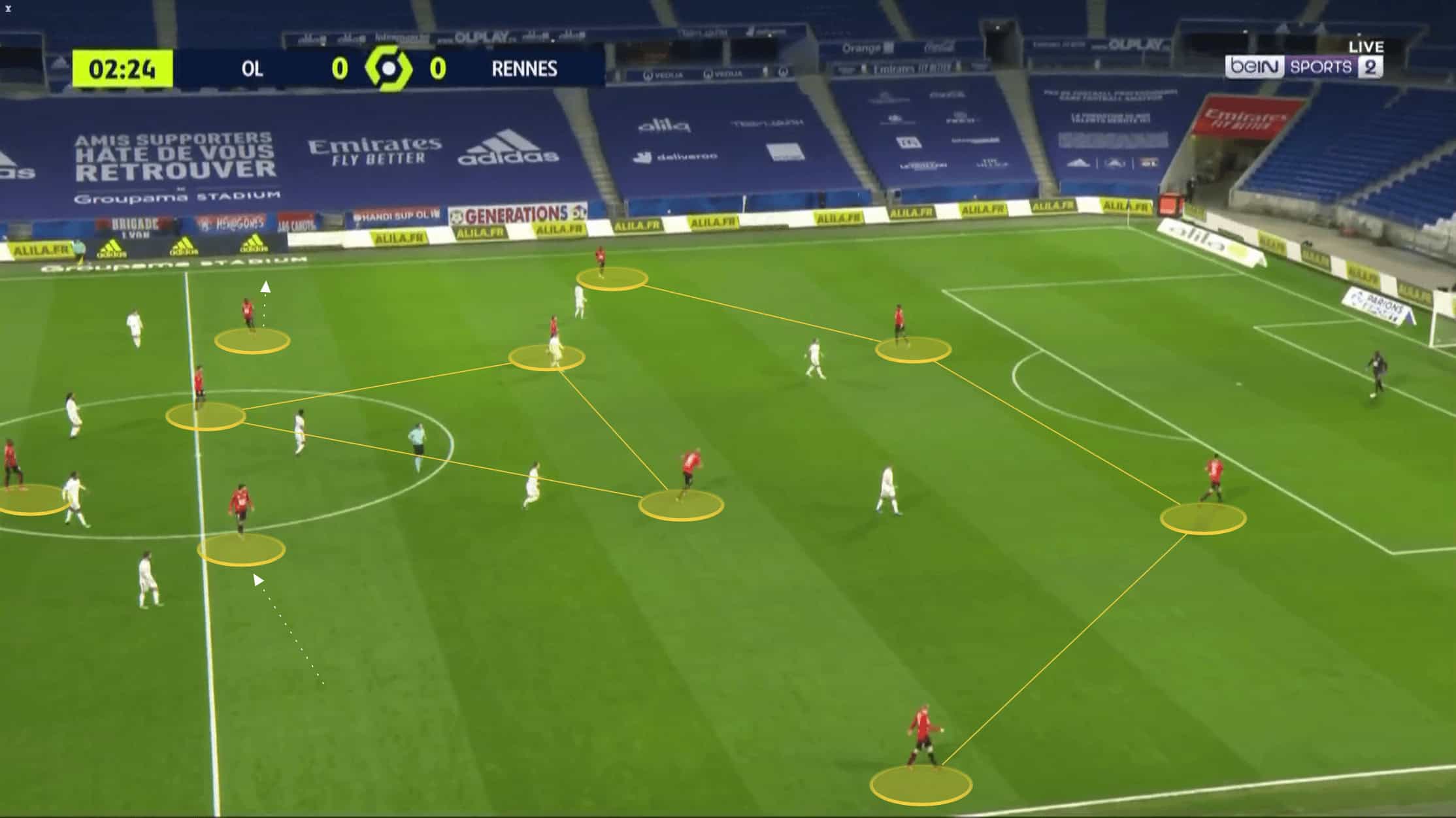

Their shape isn’t as rigid as the previous image suggests, and in possession we will generally see it look a little something like in the next image.

Note the full-backs high positioning, and Martin Terrier coming far inside, far more so than his right-winger teammate, Jeremy Doku.

We will explain the reasoning for this shape over the course of this analysis.

Shape in possession

Before we look at any of the patterns of play we should define their shape in possession. We’ve seen the overview of this in the introduction where the formation was highlighted.

Against a high press their shape is less interesting, just having the full-backs spread wide, and centre-backs do likewise, whilst the pivot sitting just ahead, potentially closely supported by another midfield in a double-pivot, as they look to stretch the opposition press.

However, when facing a less intense press, their shape helps them create direct attacks starting from the back, a consistent threat from either flank, and the opportunity to overload most teams in central midfield.

Again, the centre-backs push very wide, which in turn allows the full-backs to push high. The knock-on effect of this is it gives the opportunity for the wingers to tuck inside. Terrier looks to push almost into a central-midfield position, which we will look at momentarily.

This leaves Truffert occupying the left wing often by himself. He is a respectable outlet in his own right, however, Rennes generally prefer structuring their play down the right flank. This is down to the dual-threat offered by Hamari Traore and Jeremy Doku. Individually, both of these players are dangerous but as a duo, they can provide a problem for any side. Being a side that have a lot of possession, teams will naturally look to sit deep, and it’s not surprising to see that Rennes put in a high number of crosses, with over 17 per 90. Yet of these, in total over the course of the season, 292 have come from the right flank compared to just 196 from the left.

We can see how heavily they favour the right side by looking at the following pass map from their recent loss to Nice.

Rennes are able to commit their full-backs so high, and push their centre-backs so wide, due to their pivot’s deep positioning.

One of the central-midfielders will often drop between the centre-backs, or at least close enough to give central protection against the transition should Rennes lose possession. Leaving two centre-backs by themselves would obviously be a risky move, but the central-midfielder gives them a back three, which is far safer.

This shape allows the full-backs the freedom to both push on more than they would be able to if there wasn’t this deep-lying pivot. With Nzonzi often dropping into this area, and therefore leaving two central-midfielders, there’s the risk that Rennes would have to focus all of their build-up in wider areas if the opposition played with a midfield three themselves. With a 2v3 it would make more sense for Rennes to play wide and avoid being outnumbered centrally. Rennes’ two central-midfielders in this space, most often Camavinga and Bourigeaud, are given a decent amount of freedom. One might drop close to the back three, and one stays high or they may almost work as a double-pivot themselves if Nzonzi is totally out of the central zone.

Terrier will drift inside from the left-wing and ensure there is still a midfield three if Nzonzi is part of the back three. Due to the full-backs pushing up, there is still a threat on both wings despite Terrier coming inside.

Terrier’s free role also means he might push up to join the lone centre-forward, and when he does this, the central presence of a front two keeps the opposition centre-backs tight. However, with the presence Rennes have on both flanks, particularly on the right side, this can lead to the opposition defence being stretched. We will touch on the impact of this in more detail in the next section.

Playing from the back

Rennes are happy to play deep inside their half, and build-up inside their 18-yard-box, whilst keeping a centre-forward presence high up the pitch. Along with the full-backs providing width this leads to masses of space in the midfield area.

Their centre-backs as a result are happy to look to punch the ball through the lines, either directly into the front line, or out wide to the full-backs.

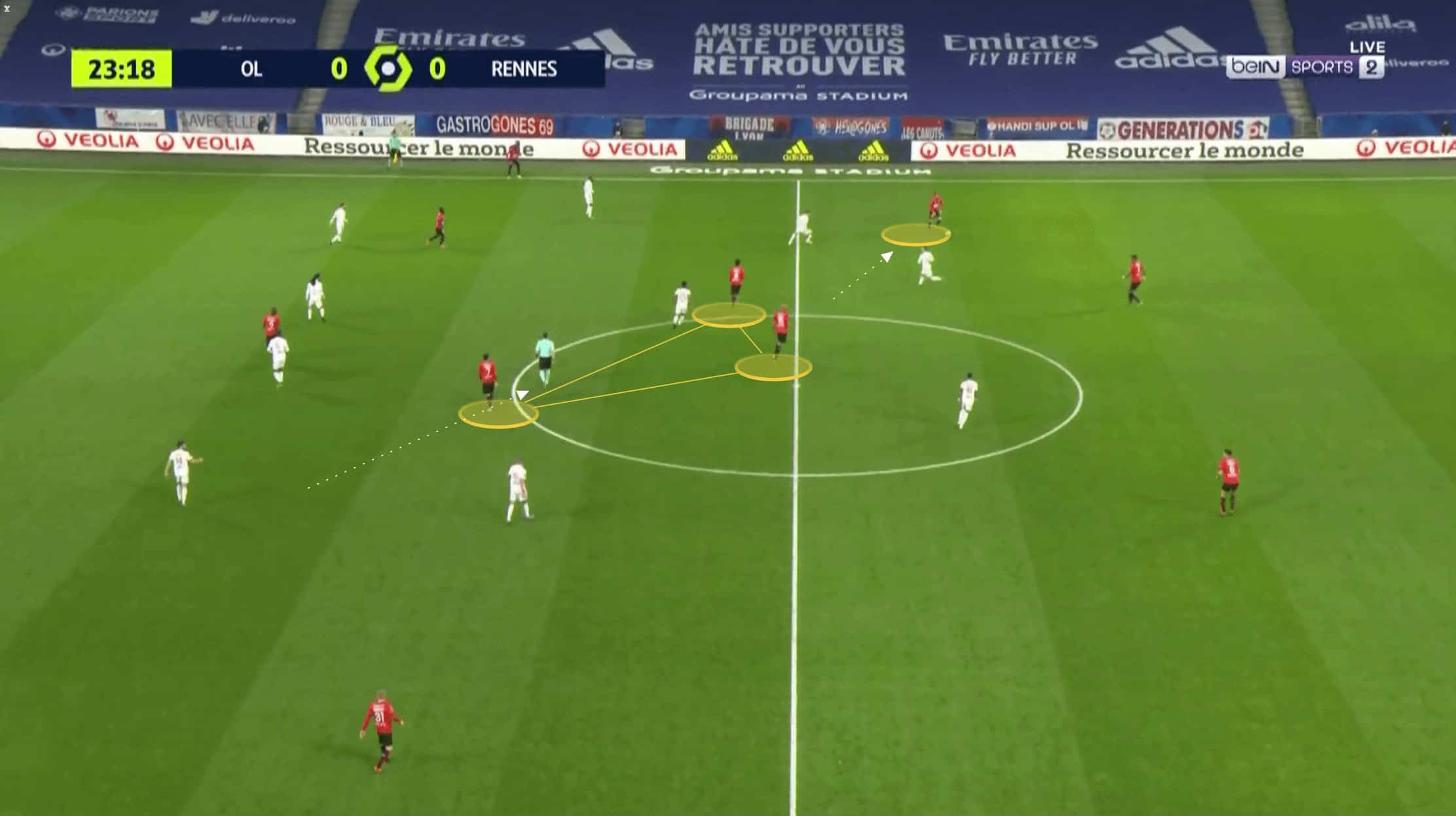

At the same time, they can easily isolate opponents and advance the ball with simple triangles. The following image shows how the centre-back left-back and central-midfielder construct the triangle, whilst the ball-carrier also has the option to punch the ball straight into the forward line, either to feet, or over the top to the run in behind.

The centre-backs often look to bypass the press by playing directly in the half-space. The likes of Doku and Terrier might drop into this area, or one of the central-midfielders might loop behind the opposition midfield to try and receive in this space themselves. In the next image we can see what it looks like as Doku drops into the space

But if he chooses to stay wide, a midfielder can just easily hit this space behind too

The width provided in attack also provides a simple option over the top for Rennes’ centre-backs to look to hit with a direct ball, straight through the half-space.

If this pattern occurred on the left-flank, the winger, Terrier, would drop into the half-space to look to receive, and then the forward Guirassy would make the run in behind, from the same angle as Doku. Due to his positioning though, it’s a slightly different run to Doku’s, where it could potentially take him away from goal rather than towards.

The effect of both of these runs is designed to unbalance the opposition backline. We can see how in the previous image, the right-back would likely follow Terrier’s run and this would leave space behind for Guirassy to run into.

However, Terrier’s run comes from a higher starting position where he isn’t being marked by a midfielder, but a defender. Therefore, if he isn’t followed into this space by the right-back, then the pass over the top isn’t on. However, Terrier can receive the ball in space. On the other hand, if he’s closely marked and the ball goes over the top, then he’s drawn a defender out of the backline and unbalanced the opposition defence. We can see this pattern occurring in the next image from their recent fixture against Lyon.

Terrier can create this kind of opportunity for himself by moving back out to the left flank as well.

If Truffert isn’t positioned as high as he sometimes might be, there is room for Terrier to shift out again. As he does this Guirassy drops deep looking to receive the ball to feet, but Terrier now has that angle to run in behind this space.

Midfield overloads

Due to the presence on each flank presented by the high full-backs, as well as Doku staying pretty wide, Rennes can commit more players to the midfield. A lot of teams will look to match them in this area by fielding three central-midfielders themselves. If they go with a midfield two, then it’s easy enough for Rennes to overload in the central channel. However, when it became a 3 v 3, they could still gain the advantage, due to Terrier’s presence.

Note the presence of the centre-forward in the previous image. It’s vital he positions himself where he does, in between the centre-back and right-back of Lyon, for this prevents the full-back from following Terrier inside. Rennes’ three central-midfielders engage in a quick interchange, drawing the Lyon midfield forward, and Terrier is able to simply drop into the 10 space to receive the ball beyond the lines.

The midfielders will look to shift across the width of the pitch and support the wide areas too. Particularly in the case of the right side where Traore and Doku are already closely positioned to one another. Their joint presence is usually enough to draw an opposition left-back out to challenge them. If we remember, the central presence in this scenario of Terrier and Guirassy keeps the opposition centre-backs narrow, and leaves a gaping hole in the half-space.

Rennes’ midfielders, in this case Camavinga, will wait for a direct pass from the back towards the right wing, before hitting this space, and creating an overload on the opposition left-back.

Conclusion

Whilst they have patience in possession, there is still a directness to their approach. Rennes do not rush this pass, however. A lot of their passes are signed to allow the attacking players to get into position whereby they can structure these kinds of direct moves. The ball over the top wouldn’t work if there wasn’t a threat of the player coming into the half-space to receive a shorter, but still line-breaking pass directly from Rennes’ back three. With Rennes demonstrating their inclination to play this kind of pass, opposition defenders can be more easily lulled forward, and that’s what makes that direct pass over the top more devastating.

Otherwise, they have a fluid formation, but with key instructions for certain players to help them build-up successfully. They still provide width, potential overloads on the right flank and in the middle of the pitch, and their back three created by the pivot dropping in gives them a solid, confident, ball-playing unit from which to build their attacks from.

![Arsenal Vs Manchester United [2–3] – Premier League 2025/2026: How Michael Carrick Punished Mikel Arteta – Tactical Analysis 24 Arsenal vs Manchester United](https://totalfootballanalysis.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Arsenal-2-3-Man-United-tactical-analysis-350x250.png)