We’ve all heard the saying that “timing is everything.”

That certainly holds true for the most fluid attacking sequences. Moving from one phase of the attack to another is cued by so many factors, such as the positioning of the opponent and the in-possession team’s established superiorities.

In this tactical theory article, we’ll look at the cues for progressive actions in each of the first three attacking phases. We’ll start with building out of the back, progress to how we connect our lines in midfield and then finish with an analysis of final third actions. The objective is to describe systematic cues in each third of the pitch in open attacks. Counterattacking situations are typically straightforward (see the space, attack the space), so this tactical analysis will focus on contextual examples of progressive actions against structured presses.

Building out of the back

As we begin this analysis, we want to show different methods clubs implement to construct their attacks from the back. We’re specifically looking at different means of playing out of the back, noting patterns that emerge from those scenarios. The goal is to identify superiorities the in-possession team is trying to construct and note how they engage the opponent to realize the objectives of their attacking tactics.

Pulling an example from a recent tactical analysis, we’ll start with the relation of low and high lines during the build-out phase. The four-in-one image comes from the Allsvenskan side IFK Värnamo. The beauty of the sequence is that we get a clear visual of Värnamo’s first two lines and the gap that emerges between the opposition’s backline and midfield.

As Värnamo start their attack, the objective is to push the opposition high up the pitch, committing them to the high press and increasing the distances between their lines. Pulling the opposition forwards higher up the pitch leaves the midfielders and a difficult situation. Either they step higher to maintain their distance from and support of the forwards, leaving more space behind them, or they remain in a deeper position, leaving the forwards to carry out the high press on their own. With the first option, space opens up between the defending team’s backline and midfield, whereas the second example increases the gap between the midfield and forward lines. It’s a lose-lose situation.

Värnamo was successful in creating a gap between the backline and midfielders. Playing a progressive pass into the path of their checking forward created an opportunity for a more direct attack. So, the indirect build-out served the purpose of creating an opportunity for a more direct attack higher up the pitch.

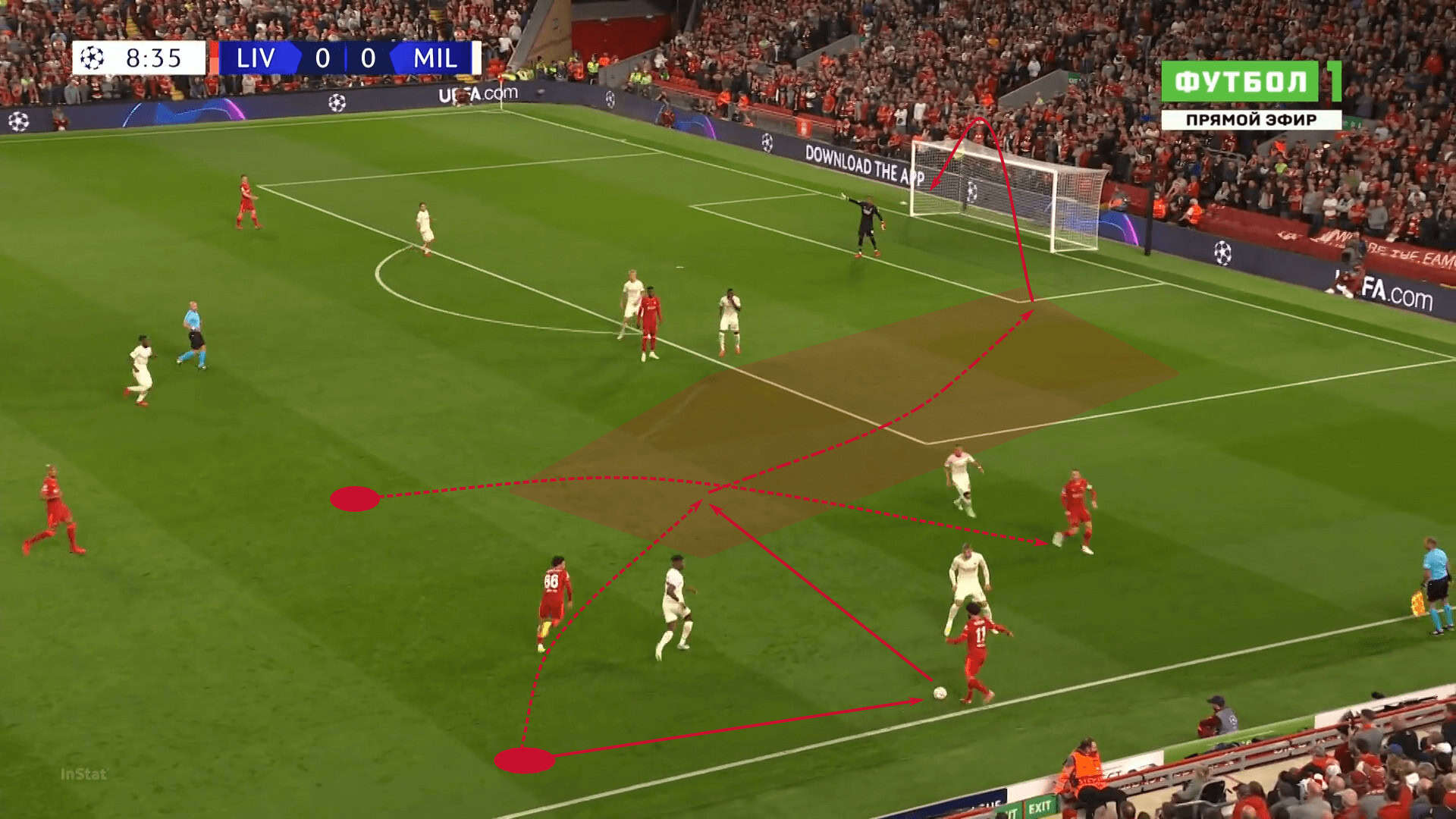

While Värnamo was successful in creating a large gap between the opposition’s backline and midfield, attacking the space between the opposition’s first two lines can be equally effective. Whereas in the Värnamo example the ball circulation along the backline draws the opposition higher up the pitch, our second image shows a more resolute AC Milan side defending in a disciplined mid block.

Liverpool’s efforts to draw the Serie A champions higher up the pitch was unsuccessful. They had to find another way to engage I Rossoneri. Fabinho provided the answer.

Initially positioned between the two forwards, he then checked between the first two lines and offered that first line-breaking pass. As he received the ball, Milan attempted to close space quickly and prevent him from playing forward. However, Fabinho was able to receive on the half turn and play forward, breaking the second line of AC Milan’s 4-4-2 mid-block. Breaking the second line effectively beat the Milanese press, allowing Liverpool to swing the ball into the left-wing and progress into the final third.

In both examples, the in-possession teams were searching for ways to unbalance the opposition along the y-axis. The more aggressive the high press, typically the more stretched the defending team’s lines. As they become stretched, gaps in their defensive structure emerge and support is less timely.

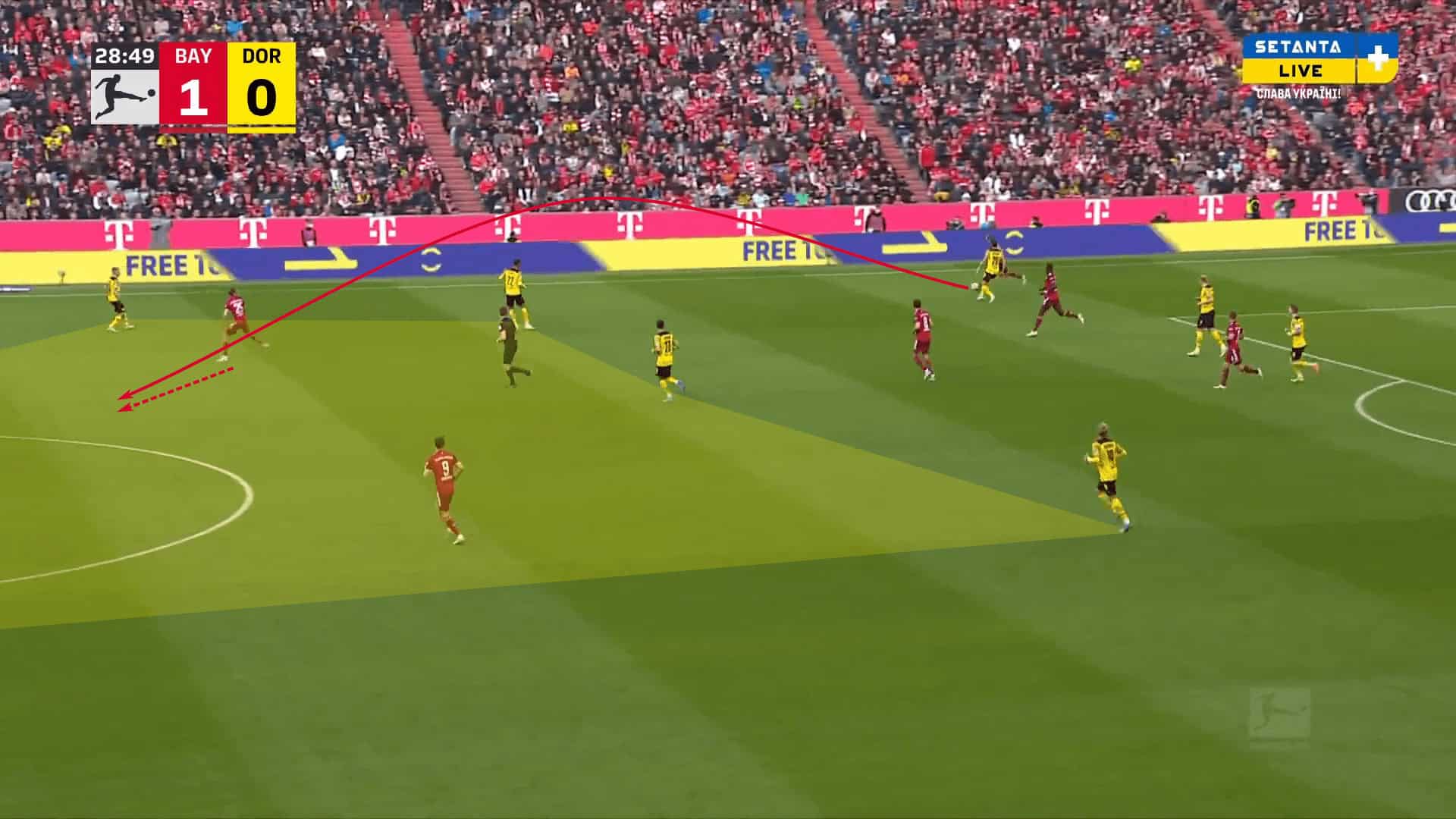

Top sides like Bayern Munich use this concept with remarkable efficiency. Given the quality Manuel Neuer offers at the back and that the German side is blessed with an abundance of press-resistant centre-backs, they can essentially bait the opposition to overcommit in the high press. This is exactly what happened against Borussia Dortmund. As Der Klassiker raged on, Der BVB frequently pushed five to seven players high up the pitch to pressure the Bavarians into a turnover.

Knowing that Dortmund’s first two lines had pushed into the final third, Bayern’s attacking midfielders advanced up the pitch rather than dropping deep to offer short-range support, sending a cue to their deepest teammates to target the space between Dortmund’s backline and mids.

Each of these first three cases were instances of unbalancing the opposition along the y-axis. By increasing the distance between the opponent’s lines, the team in position could more effectively target the spaces between the lines.

But it’s not always possible to play through the opposition. Having a plan B in your team’s arsenal is necessary. Since our first few examples focused on stretching the opposition vertically, we’ll now look at an example where playing around the opposition was the most effective way forward.

Returning to Liverpool versus AC Milan, we find the Italians very organized and narrow in their mid-block. Liverpool’s centre-backs are leading the build-out, gradually pushing from their defensive third into the middle third of the pitch. They want to engage Milan’s forwards to create space between the lines, as seen in the last instance, but this time I Rossoneri don’t take the bait.

Without the conditions to play through the Milan defence, Liverpool must work their way around it. Trent Alexander-Arnold’s positioning is interesting in this sequence. As Virgil van Dijk looks to play forward, he would typically expect Alexander-Arnold to take a wider starting position, improving the angle for the pass.

However, TAA remains slightly more narrow. Given his positioning behind AC Milan’s midfield line, he seems to give the cue that he wants the ball on his back foot so that he can attack the space behind him. Van Dijk hits his pass with a lot of pace, bypassing two lines and springing Alexander-Arnold into the opposition’s half of the pitch.

The Liverpool example was fairly simple. Alexander-Arnold offered an angle to play around the AC Milan defence and van Dijk played him. There is very little resistance from Milan as their focus was to deny passes through their lines.

Let’s look at an instance in which the opposition is pressing the build-out more aggressively. In this case, we have Borussia Dortmund in possession and Bayern Munich in the high press.

From a numeric standpoint, Bayern has committed eight field players to their left side of the pitch. The goal is to seal Dortmund into the wing and deny outlet passes.

At this stage in the game, Dortmund had suffered many unsuccessful build-outs, routinely turning the ball over in their own half of the pitch. For the match, Bayern recorded 17 high recoveries to Dortmund’s seven. The high press suffocated the Dortmund build-out, leading to short-field counterattacks for the Bundesliga Champions.

However, in this instance, Dortmund’s clever wing combination play helps them overcome the Bayern press. Marco Reus spearheads the sequence. As Dortmund built out on their right side, they quickly find themselves in a situation of numeric equality. But notice how the attacking team’s spacing created a pocket in the middle of the high press.

Reus left his central position, darting into that space. As the play evolved, a simple triangle was formed between the captain, Julian Brandt and Marius Wolf. When Reus received, he played the ball forward to Brandt, who then set his pass into Wolf. When that second pass was underway, Reus noticed the gap on the left side of Bayern Munich’s backline. Brandt’s deep, wide check created that space. With Bayern pushing higher and wider to engage the Dortmund build-out, Reus made his run from deep, cueing Wolf to play him a pass over the top.

A simple up-back-over pattern allowed the away side to beat the press. Knowing that numeric equality and Bayern Munich’s highly structured press would make it difficult for Dortmund to play out of pressure on the ground, the coordinated movements of Brandt and Reus forged a new path forward. It’s not enough that Wolf play that pass over the top. Instead, the objective was to release Reus behind the backline with optimal attacking conditions provided by the spacing of Brandt and Erling Haaland, who is positioned centrally. That extensive spacing between the two forwards created the space for Reus’s run.

If there is an emerging theme in this tactical analysis, it’s that reference points and coordinated movements are the means through which positional play is executed. Using one’s reference points and movements to create superiorities allows a team to more effectively implement their game model. Those relationships matter.

Having looked at the build-out, let’s move on to the middle of the pitch.

Connecting the lines through midfield

One thing to re-enforce is that this tactical analysis is specifically addressing non-counterattacking situations in open play. A core principle of the counterattack is that when space is available it should be taken quickly, particularly if numbers are equal or favour the team in possession. We’re not concerned with the counterattack in this article. Instead, our focus is on open-play tactics against more structured opponents.

As we progress, you’ll notice recurring themes. One of those ideas is creating space between the lines. Just as we saw in the previous section, teams that can effectively target the space between the lines not only bypass parts of the opposition’s press, but they also create better attacking conditions for the subsequent move.

Take this example from Real Madrid’s legendary Champions League victory over Manchester City. As the EPL side settled into their mid block with a midfield line of confrontation, Real Madrid’s centre-backs were responsible for the team’s attacking tempo. With the Cityzens taking a more passive, zonal approach, Real Madrid’s deepest players patiently circulated the ball as they awaited an ideal moment for a line-breaking pass.

Nacho is the one to play the forward pass, but it’s Luka Modrić’s positioning between the lines that determines the next course of action. With Modrić moving underneath Benzema, who is stretching the City backline, the Croatian was able to receive on the half turn, pivoting into a forward-facing position.

His next pass is into Vinícius Júnior in the left-wing, giving Real Madrid a 3v2 just outside of the box. While the numeric superiority is important and Modrić is merely the facilitator, notice Manchester City’s midfield spacing. As the ball travels to Modrić and he completes his turn, the City midfield collapses on him. As they close down their distances to the ball, that creates more space in the wings for Vinícius Júnior. It also frees Ferland Mendy to push higher up the pitch with an overlapping run. Before Gabriel Jesus pushed inside, numeric equality was the likeliest scenario.

However, with Modrić receiving in the half space and drawing Jesus away from the wing, Mendy was free to continue his run and link up with Vinícius Júnior. Even the overlapping run is designed to force a decision upon the opposition. If the defender follows the runner, space opens up for the first attacker to dribble centrally. If he stays with the first attacker, a pass to the overlapping player gets him behind the line.

While the Real Madrid example offers an inside-out movement to get the ball at the feet of their dynamic dribbler, AC Milan offers a nice example in the reverse.

Brahim Diaz starts the sequence with a pass into Alexis Saelemaekers. Notice the Belgian’s positioning between the lines. He’s situated in the central channel, closely connected to both Rafael Leão and Ante Rebić.

The run of Rebić is especially important. One possible outcome is to play him directly with a ball over the top. The second, which is what transpires, is that his run pulls Joe Gomez away from the central channel, leaving Saelemaekers alone and with a clear path to dribble into Zone 14.

As AC Milan approached the Liverpool box. Saelemaekers’ slipped the ball into Leão, who played the key pass into Rebić.

The big takeaway in the AC Milan sequence is that the wide attack produced a move into the central channel. From that position, Milan could use their tightly connected central network to overcome the backpedalling backline. Saelemaekers’ central positioning helped set the tempo. Between his positioning and Rebic’s run behind the backline, the timing of the move was perfectly executed. Rebić unselfishly sprinted behind the backline to draw Gomez away from his Belgian teammate. Though he wasn’t immediately involved, he was able to finish the move with a bending shot.

Those first two examples offered sequences where the ball moved from one vertical channel to the next. Let’s open up the range and look at switches of play, both partial and full.

Both examples come from the Real Madrid versus Manchester City second leg. First, we have City cleverly drawing the Spanish side into the wings, leaving them unbalanced along the x-axis. With Real Madrid committing so many players to the ball, Bernardo Silva was left entirely unmarked.

Meeting no resistance, the Portuguese playmaker carried the ball over 40 m, running at Nacho. The Real Madrid backline slowly shuffled back in an attempt to delay the Man City attack, but the pace of Bernardo’s carry didn’t allow the opposition midfield to recover. The play culminated with a Bernardo Silva assist to Riyad Mahrez, briefly giving the Cityzens a two-goal cushion.

The big takeaways from City’s attack are their ability to retain possession even while under heavy pressure and the understanding that if the opposition’s pressure increases and that minor sense of anxiety that accompanies closing space starts to appear, those are natural indications that it’s time to play out of pressure. Amazingly, Bernardo had the good fortune to be clear of the entire Madrid team, and he makes the most of it by providing the assist.

That’s an example of a partial switch as the ball travelled through two vertical channels. In the next sequence, it’s Real Madrid in possession and City that has become unbalanced near the ball. Notice the coverage of the City press. They’re extremely compact, both vertically and horizontally.

Rather than forcing the ball into Vinícius Júnior’s feet and hoping for some magic, the ball is played back to Toni Kroos, who plays the long diagonal from the left-wing to the right.

In both cases, Real Madrid and Manchester City used possession as a means of drawing the opposition into the wings, then quickly switching the point of attack to exploit space elsewhere. Numbers near the ball and spatial density are built-in cues for the attacking team. As the sequences start, the in-possession side has plenty of space to operate. However, as the opposition regain their defensive shape and start to condense the playing area, the challenge for the attacking team is to find their way out of pressure and funnel the attack into more open territory.

Defensive tactics can make the vertical spaces very small, but the only built-in constraint to manage the opposition’s width is the field’s dimensions. Switching the point of attack to exploit width is much easier than manipulating the opposition’s positioning along the y-axis.

One of the contemporary solutions for creating and exploiting space through verticality is the use of high, central overloads. Interior wide forwards or attacking central midfielders coordinate their movements with the centre forward to initially occupy a high central position to then manipulate the structure of the opposition’s backline, as well as any supporting midfielders.

In this Bayern Munich example, the Bavarians have the ball on the left-wing with three players in a high central position. Two of the three make hard runs into the left-wing and half space while the third stays central. The runners offer the cues for progression. As they burst into wider positions, it’s the responsibility of the first attacker to read the opposition’s response. If they maintain their zonal marking, that’s typically a sign to play their teammates into the wings. Should the opponent follow the runners, valuable real estate opens up centrally.

That’s exactly what we see here. The Dortmund defenders track the runners, giving Bayern Munich a lane to move the ball centrally. Rather than the forward, Jamal Musiala, collecting the ball, he dummies it into the path of Leon Goretzka, leading to a blameworthy, unselfish crossing attempt from Thomas Müller.

As high central overloads have become more frequent in the modern game, there is more of an impetus on the central defenders to set the attacking tempo and use one player to offer width in each wing.

If the ball is played into the wings, there are opportunities for combination play with nearby midfielders and forwards. However, as the centre-backs orchestrate the attack, their first look is typically into the high central overload. If they can bypass one or two of the opposition’s lines especially by playing into their highest teammates who have support underneath, that is typically the preferred passing option. If those lanes are not available, that is a cue to keep the ball moving, often in a u-shape.

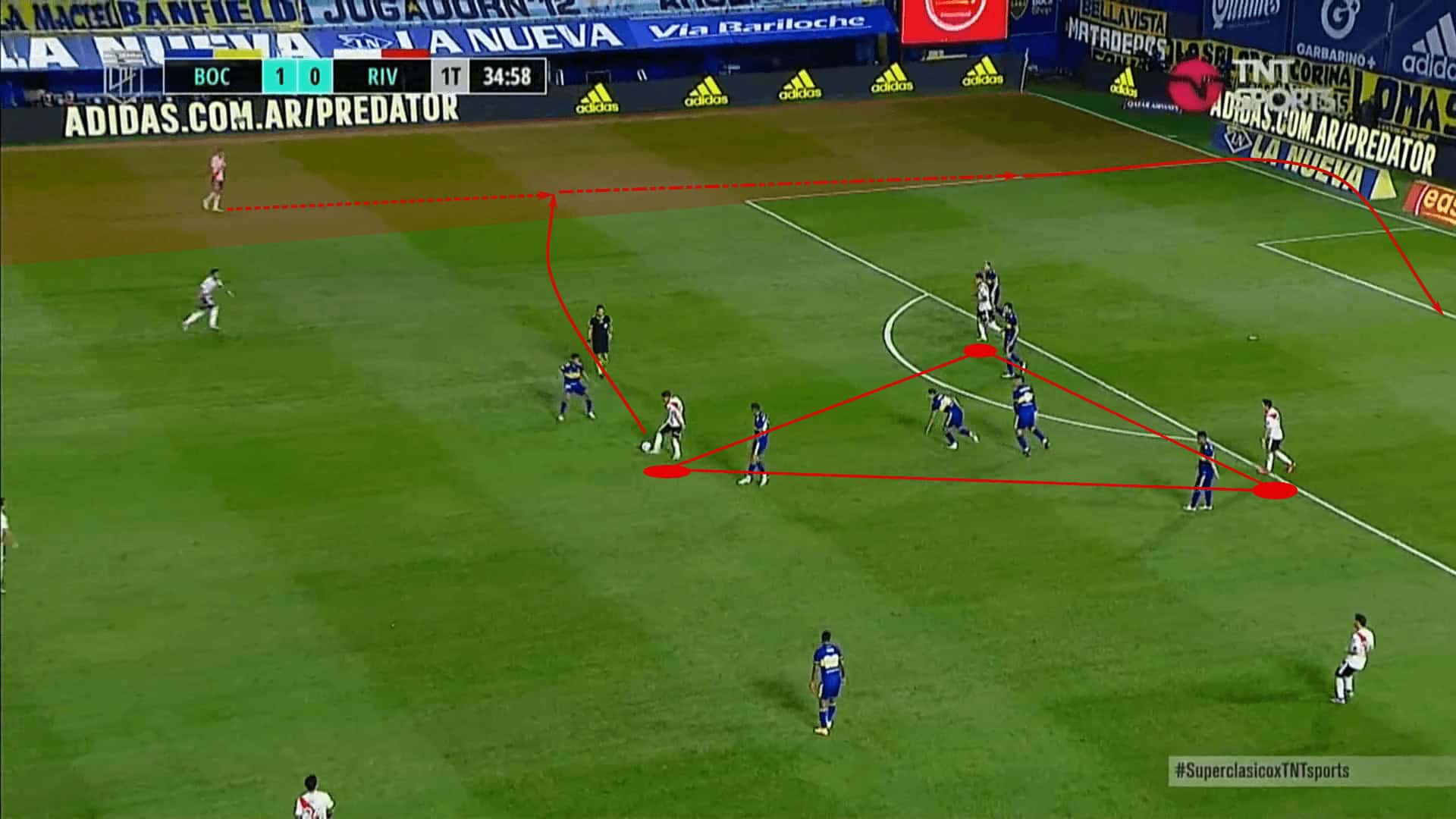

Our final image for this section shows Marcelo Gallardo’s tactics at River Plate. He will exclusively use one player on each wing as the lone width provider and use either a 2-3 or 3-2 set up at the back to safeguard his side against the counterattack and give different angles to play forward.

When those forward passing lanes are not readily available, his centre-backs are encouraged to create them. In this instance, dribble progression to pin the Boca Juniors midfield leads to a pass into River Plate’s highest line.

With Boca Juniors taking up a wider defensive shape, there were opportunities for River Plate to target their highest outlets. As the centre-backs directed the attack, they were constantly scanning the pitch directly in front of them to look for that dangerous, vertical pass.

The spacing of the opposition and positioning of teammates between the lines, closely coordinated with other teammates actively stretching the width and height of the pitch, is the scenario members of the backline have to interpret. Reading the cues in front of them, and seeing what the opposition is giving them, determines the next move.

Since each example is taking us closer to the final third of the pitch, let’s read the cues and move into the final section of this analysis.

Final third actions

When the match report comes out and fans rush to the box score, it’s the actions at this end of the pitch that will garner the headlines and produce cries of joy or mutterings of frustration.

As shown in examples from this analysis, those critical actions in the final third often rely upon less celebrated passes, dribbles and movements in the preceding two-thirds of the pitch. Disconnect the final product from a good build-out or a well-played connection in the middle third and the odds of an end product in the final third drastically decrease.

But let’s say your club, whether your relationship is that of a fan, player, coach or staff member, has entered the final third and is looking for that little bit of magic to end an attacking sequence. What are the cues for progressive actions they’re looking for? How do they use their starting positions and movements of the ball, all while meticulously balancing their four reference points, to create a scoring opportunity against an organized opposition?

The first topic for discussion is unbalancing the opposition’s backline and creating numeric superiorities. Ball and player movement are highly targeted, looking to create numeric advantages in the wings or using central overloads to connect a centre-forward with one of his teammates.

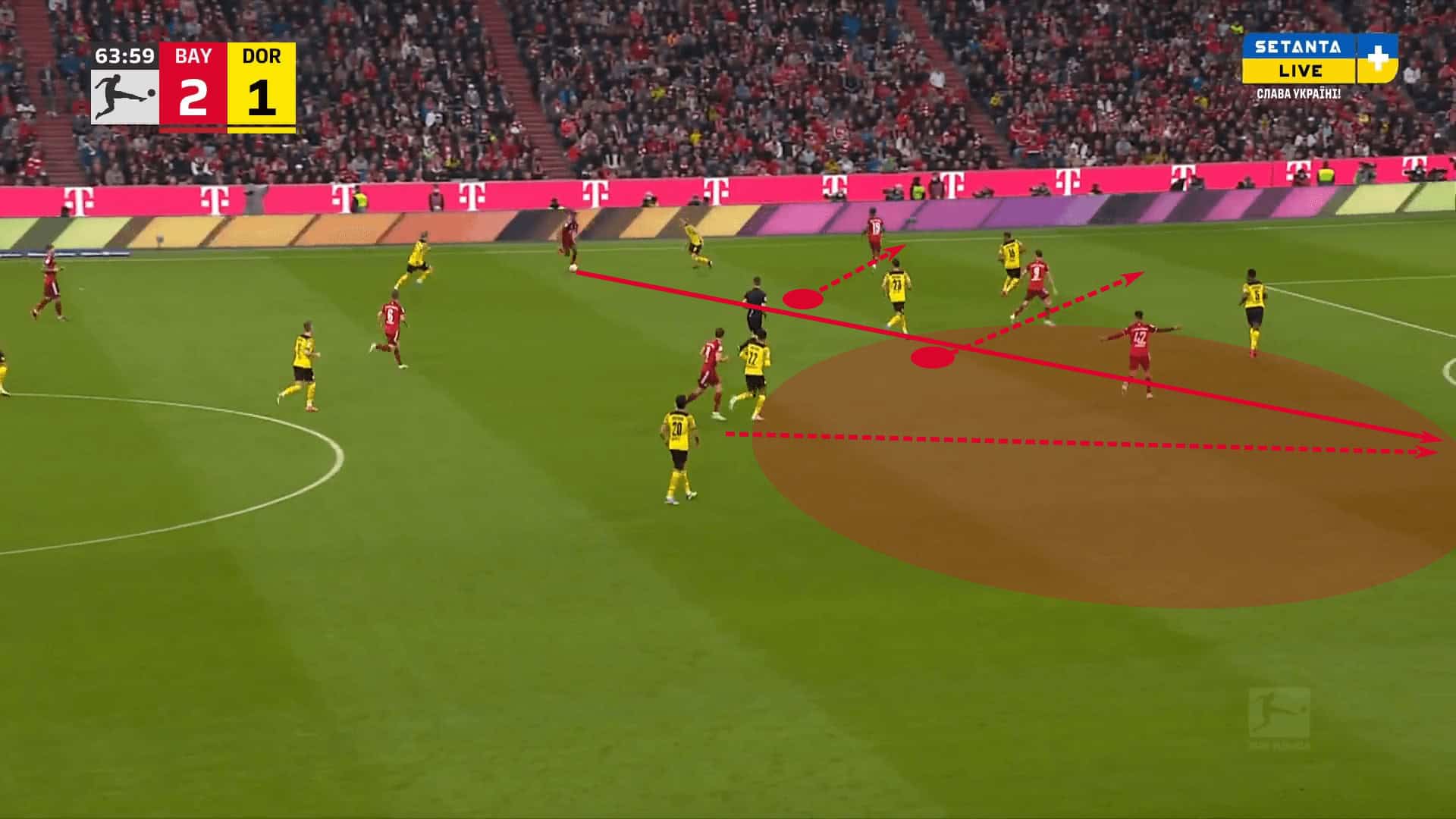

Up against a resolute Borussia Dortmund low block, Bayern Munich held the ball on their right-hand side but couldn’t progress into the box. Rather than hitting a hopeful cross, they played negative and switched the point of attack to the left half space. Lucas Hernandez was the recipient of the pass.

As the Bavarians switched the point of attack, the left-sided players were busy coordinating their movements, creating a 2v1 against Wolf on the left side of the pitch.

Hernandez’s first look was up the pitch. Identifying the numeric advantage directly in front of him, the Frenchman played the pass into Musiala. Notice the foot he plays the pass to. Alphonso Davies and Musiala created a 2v1 scenario, cueing Hernandez to play into them, then the centre-back sends a cue of his own, playing the forward’s interior foot, communicating that he should turn inside.

Musiala dribbled into the box and unleashed a shot. After a rebound and loose ball scenario in the box, the youngster capped off the play with the final goal of the game.

The setup was simple. Two players against one in a wide area. With the defender caught between the two players, Hernandez simply had to pick the better target and communicate what his next action should be with the type of pass he sent. Again, 2v1 on the left side of the pitch is a simple enough setup, but it’s the early recognition of Davies and Musiala to understand that the switch of play was coming and that they were better off basing their movements on their relationship to Hernandez rather than preparing for a run into the box. Unlike the Dortmund backline, the two Bayern players moved in connection with each other to exploit the stranded Dortmund right-back.

In this Bayern example, the sequence featured a right-sided overload, switch of play and then a progressive pass into the high targets. The pass into the targets was played into feet rather than space.

And this brings us to an important point. More often than not, it’s the actions of the receiver that cues the type of pass needed. If the second attacker is standing still or shuffling within a certain area, that signals he wants the pass to his feet. Dynamic, directional movements are indications to play into a specific space so the receiver can run onto the ball.

The Bayern Munich example gives us a scenario where the ball is played into feet, whereas this next one shows a forward who wants the ball in the space behind the backline.

This next example features peak Barcelona against Grenada. That’s Lionel Messi pulling the strings in midfield and Cristian Tello making his move from the left-wing. As Messi cut inside on his preferred left foot, Tello had some work to do. First, that Granada backline was very tightly connected. There was very little space for a through ball, so Tello’s first responsibility was create as much of a gap as possible between the right-back and right centre-back. Taking a high and wide position accomplishes this task.

While that #2/#4 gap is still relatively small, Tello knew that all eyes were on Messi. With the attacker in a high and wide position, it was difficult for his mark to keep an eye on both the player in the wing and the threat of Messi attacking Granada on the dribble right through the central channel. As Messi moved, the timing for Tello’s run was drawing near.

To ensure his run was untracked, Tello had to sync his movement with the attention, or lack of it, from the Granada right-back. As the threat of Messi’s dribble looks more and more imminent, he draws the Granada backline’s attention, cueing Tello to make his move. Out of sight, out of mind, his horizontal movement kept him onside, then he broke into a diagonal run as Messi sent the through ball. The sequence was perfectly timed and perfectly executed.

As a result of the Barcelona Golden Generation’s dominance, elite teams routinely find themselves up against the low block. Finding a way through the sea of bodies has become a top objective many top clubs around the world. Creating gaps for through passes and progressive runs, like we saw in the Barcelona example, has become an art.

Take this Liverpool example. Mohamed Salah is on the ball and he was initially joined in the half space by Alexander-Arnold. James Milner was the nearest midfielder on the play, positioned in the right half space. As the ball arrived at Salah’s feet, Milner ran beyond the Egyptian to take up the highest position of the three.

Where the captain goes, so does the opponent. Milan chased Milner into the wing, creating a gap in the half space for Alexander-Arnold to run into. The rotation was seamless, clearing the half space for the right-back’s dribble into the box and goal.

Also note that even though these three are tightly connected, the supporting players are deep in the right half space to prevent the counterattack and high in the central channel to pin the centre-backs centrally. Without direct involvement in the play, those two players give Liverpool protection if the ball is lost and create the spaces they want to attack.

Manchester City are the kings of such movements. Their ability to enter the box through the half spaces is unmatched in the global game. Whether it comes through dynamic positional rotations, like the Liverpool example, or wide overloads with several ways to enter the box, no one does it better.

Our City example comes against Birmingham City in a cup game. Though outnumbered 4v5, Man City’s qualitative and socio-affective superiorities helped them retain possession despite BCFCs best efforts, as well as spring a runner into the box.

That runner was Kevin De Bruyne, whose movement allowed him to receive a pass at the interior portion of the right half space, then play a superb cut-back cross for a Manchester City goal.

One of the biggest takeaways from that example is City’s understanding of their quality. Even when outnumbered in a tight space, there was still the understanding that they could retain possession while also looking to break behind the opposition’s backline. Possession served the purpose of creating gaps to run into and the accompanying pass. Ball movement was quick and possession secure throughout.

Wide overloads with half space entry into the box have become very common at the top levels, but there’s also a school of thought that limits the number of players the in-possession team dedicates to the wings. Rather than creating numeric superiorities in the wings, these teams will typically get their width from one player on each side of the pitch. The remaining eight field players will span the width of the box, giving their side control of the centre, just as you see in chess. These teams typically field interior forwards rather than traditional wingers when playing a three-forward system. They may even play a 2-1 or 1-2 with three interior forwards, which we see with Gian Piero Gasperini’s Atalanta.

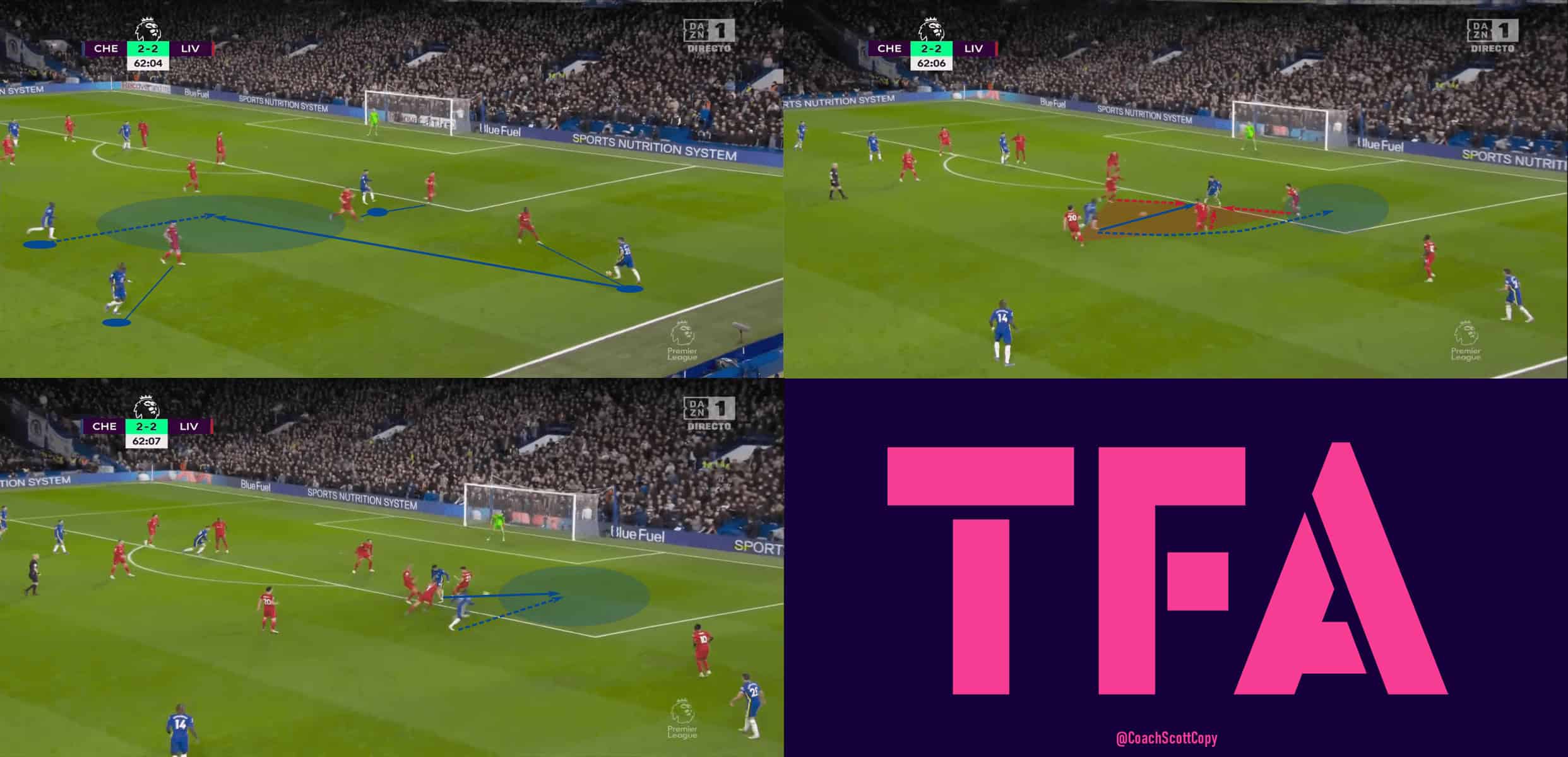

Chelsea is another club that uses a 3-4-3 with three central forwards. Getting their width from the left and right midfielders, Chelsea aims to control the middle of the pitch. That objective forces the opposition to use a more narrow defensive structure. When Chelsea can’t penetrate centrally because of the opposition’s narrowness, the Blues then know to play into the wings to increase the width of the opposition’s lines.

As opponents quickly slide their lines into the wings, Chelsea’s central players are actively searching for gaps in their lines. A pass into the wings offers that mental trigger to search for space centrally.

In our three-in-one image, Chelsea has the ball in their right-wing, but are very actively searching for space to exploit centrally. The narrow blue lines indicate which opponents the Chelsea players are occupying. Christian Pulisic’s first few steps attacked space behind the backline. With him occupying two players, N’Golo Kanté saw his opportunity to move higher in the right half space. The pass goes to him and he combines with the checking Pulisic, whose clever flick plays Kanté into the box.

Dominate centrally, stretch the opposition through the isolated wingers and run into central gaps. Simply stated, but it’s a basic pattern used by many teams playing a 3-4-3 or some variant of that system.

The same basic principle converts to a four-back system as well. The best example I’ve come across takes us to South America where Gallardo’s River Plate create a 2-3-5 or 3-2-5 attacking shape from their base 4-3-3 formation.

A refreshing aspect of Gallardo’s tactics is that when a forward pass is available, it’s typically taken. His side controls the centre of the pitch and is very structured with its high and low overloads. River Plate’s passing networks are tightly connected and positional rotations limited. Play is quick and often direct, but in a very controlled manner, much like I described in my tactical analysis of direct possessions.

One differentiator with a high central overload and single width providers on each side is that it can be used as a vehicle for sending and meeting crosses with numbers of situations in the box. As River Plate plays into their high central overload, if they cannot continue their movement up the pitch, it signals the players to play to the free man in the wings. Once the ball is played wide, Gallardo’s players instinctively know to make their runs into the box. They typically enjoy numeric equality, which is an exceptional state for attacking a cross.

As this analysis on cues for progressive actions comes to a close, every example to this point has showcased high-level attacking tactics implemented by immediate networks within the team. To close the article, let’s shift to the other end of the scale and look at a dying breed in the modern game, the dribble-dominant wide playmaker.

There’s no better example than Vinícius Júnior. Prior to his breakout campaign in 2021 / 22, the consistency of Real Madrid’s wing production limited their attacking output. The connection between Vinícius Júnior’s breakout season and Karim Benzema’s Ballon d’Or worthy year is both obvious and inseparable.

When a team is blessed to have such a dominant dribbler in their squad, the immediate cues to the remainder of the team are to give him space and get into scoring position.

Let’s take a look at a Vini Jr. example. As the ball is played into him in the wings, he had exactly what he was looking for; he and his opponent were isolated in the wings with no support for either player. It’s a true 1v1 dual with tremendous stakes. Notice the three Real Madrid players centrally. None of them moved towards the left-wing to offer Vinícius Júnior support. The attacking conditions greatly favour their teammate, so they trust him to use his dribbling talent to win the duel.

And that’s exactly what happens. Vinícius Júnior runs by Dani Alves who understands the implications of his loss. Rather than letting his fellow Brazilian have a run at the next defender, leaving Barcelona 3v4 and backtracking towards their goal, he made the right decision and hacked Vinícius Júnior to the ground, earning a yellow card.

Cues for progressive actions are often associated with quick ball circulation and dynamic movements within a team’s attacking structure. These are also the most trained moments because of their complexity. This example with Vinícius Júnior belongs to a bygone era. 1v1 duels are not contingent upon passing networks or movement patterns, just the talent and willingness of the attacker to run at his opponent.

As dribble dominant players make their moves, the signal to the rest of the team is to base their movement either on a potential loss or that best-case scenario, a 1v1 win that throws the opponent into chaos, leaving gaps for the attacking team in the most dangerous parts of the pitch.

It’s brute force, an old-school duel and a moment that gets you on your feet. There’s no more tense moment in a game than when your opponent’s dynamic dribbler has the ball at his feet and he’s ready to have a go.

Conclusion

And exhale.

For those of you who made it to the end, give yourselves a pat on the back.

On a purely selfish basis, the objective of this article was to put thoughts on paper in order to better present them to my players. Working through the first three attacking phases, the effectiveness of our team’s possessions will rely heavily on their understanding of in-game patterns, contextual movements and understanding the timing of those progressive actions.

Our game is fast-paced and at times chaotic. Our players will often see the game with clouded vision, which you are likely experiencing as you finish reading this article. Removing the haze and delivering a more clear vision of the game requires us, as coaches, to help our players understand what to look for in possession and when to progress to the next phase of the attack.

Break the game into these moments with their accompanying visual cues.

Uncloud their vision, sharpen their understanding and enjoy your team’s growth.

![PSG Vs Newcastle United [1–1] – Champions League 2025/2026: A Tactical Arm-Wrestle In Paris – Tactical Analysis 29 PSG Vs Newcastle United [1–1] – Champions League 2025/2026: A Tactical Arm-Wrestle In Paris – Tactical Analysis](https://totalfootballanalysis.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/PSG-Vs-Newcastle-20252026-350x250.png)

![Napoli Vs Chelsea [2–3] – Champions League 2025/2026: How Game Management Cost Antonio Conte – Tactical Analysis 31 Napoli Vs Chelsea [2–3] – Champions League 2025/2026: How Game Management Cost Antonio Conte – Tactical Analysis](https://totalfootballanalysis.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Napoli-Vs-Chelsea-20252026-350x250.png)